This is part one of the primer for Millennium Fighting Arts Presents: Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2000. Read the previous entry (Intro) here.

In 1997, Nobuhiko Takada sacrificed his stardom to establish PRIDE Fighting Championships as a brand that could survive on its own merit. In 2000, his dream was realized and he celebrated with a return to the very place that made him famous: the squared circle.

The 200 Percent Hope

As previously discussed on “Bom-Ba-Ye”, Takada was the founder and top star of the shoot-style wrestling promotion Union of Wrestling Forces International. Formed in 1991, the promotion was born from a conflict that split UWF Newborn into three: Yoshiaki Fujiwara’s Pro Wrestling Fujiwara-gumi, Akira Maeda’s Fighting Network RINGS and, of course, Takada’s UWFi. Each founder felt like they should be the star. Each made a bet on themselves. Of the three, the UWFi came closest to being the peak of the industry.

In UWFi, Takada and his signature style would reach stardom. By decrying other professional wrestling leagues as fake and promising that UWFi was as real as it gets, they attracted fans who were mesmerized by the differences they saw.

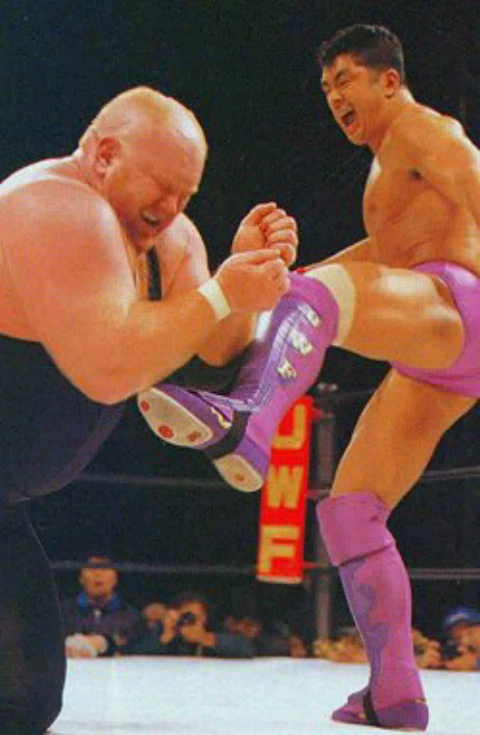

Takada’s victories over existing stars such as Bob Backlund and Vader further fed the idea that there was something truly unique to the promotion. UWFi issued challenges to every world champion in wrestling, promising that none could best Takada. For those that accepted the challenge, the promotion stayed true to their word.

When UWFi established their own championship, Takada was the inaugural victor. With Lou Thesz, wrestling’s elder statesman at the time, presenting him with the Real Pro-Wrestling World’s Heavyweight Championship, no one in attendance doubted Takada’s – and by extension, UWFi’s – legitimacy.

It’s the promise of this legitimacy that would eventually backfire.

In 1994, the Gracie family were dominating mixed martial arts. Royce had won the first two UFC tournaments – a streak including a win over Ken Shamrock – and Rickson had utterly dominated the 1994 Vale Tudo Japan tournament with a series of first-round victories. Wanting to cash in on their success, UWFi made a public offer to Rickson to compete in a match against Nobuhiko Takada. Takada, of course, was planned to emerge triumphant.

According to his 2021 biography “Breathe: A Life in Flow”, Rickson simply went surfing in Fiji instead of responding to Takada’s challenge. After being ignored, Takada and the UWFi decided to double down. They boasted that Rickson’s lack of a response was due to him being afraid to fight.

The slight caught Rickson’s attention. Finally, he responded – by saying that he didn’t do fake fights.

The UWFi team designed a stunt that would allow them to profit from the Gracies’ involvement even if they wouldn’t agree to a deal. On December 7, 1994, UWFi wrestler Yoji Anjo arrived at Rickson’s gym in California, flanked by a UWFi executive and an army of Japanese press. He had promised them that he could take Rickson on, saying he was 200% confident in his victory. On Rickson’s doorstep, Anjo laid out the challenge. To his surprise, Gracie obliged.

Following a prolonged and brutal beatdown behind closed doors, a battered Anjo was carried out by the executive, who did his best to prevent the press from taking pictures of the damage. Anjo was a bloody mess, his nose broken and his white shirt splattered crimson. To ensure they wouldn’t escape the coverage (as Anjo had begun to claim he was jumped by the Gracies), Rickson had the only tape of the fight played at a press conference in Japan. Anjo would be known as “Mr. 200%” for the rest of his career.

Changing Tides

Yoji Anjo’s dramatic failure changed the fortune of the UWFi. Their audience rapidly began to suspect that UWFi wrestlers weren’t as credible as they claimed to be. Additionally, the rise of early MMA organizations like Pancrase and UFC began to undermine their legitimacy. Takada’s failure to avenge Anjo’s beating further raised questions. As the top star, it was his duty to defeat Rickson and clear the company’s name. Instead, Takada announced his retirement.

Citing a decrease in his stamina, Takada made the statement after a title defense on June 18, 1995. No official date was given for his final match and he was still scheduled for shows going forward. Uncertainty surrounded his statement.

In the days following his announcement, conflicting information made things no different. UWFi, who were allegedly blindsided by Takada, claimed that he meant to say he would retire when he turned 35 in two years. Takada himself had hinted the retirement was a matter of months away. No one was sure of Takada’s next step.

Just over two weeks later, Takada announced he would be running for a national seat in Japan’s House of Councilors. His political bid followed in the wake of the candidacies of Hiroshi Hase and Antonio Inoki, both of whom were also pro wrestlers running for office.

Inoki was seeking re-election after founding the Sports and Peace Party in 1989 and winning a seat. Hase was seeking his first position with the Liberal Democratic Party, a center-to-far-right party which had been dominant in Japan for decades.

While Hase would win his district seat, Takada would only garner an embarassing 159,794 votes, over 700,000 less than the requirement to win a national seat. The election signified something that was becoming impossible to deny: UWFi’s cash cow was running out.

The rapid decline forced UWFi to take desperate measures. After the departure of the formerly loyal UWF original Kazuo Yamazaki to return to New Japan, the company was stunned. Yamazaki had grown dissatisfied with his position, having gone from a close second to Takada to a declining star losing to next-big-things like the extremely talented Kiyoshi Tamura, and decided to jump ship.

There was a problem, however. Yamazaki’s contract with UWFi allegedly ran through 1996, and the UWFi filed a lawsuit against New Japan in response.

At least, it seemed like there was a problem. On August 24, both companies had separate press conferences scheduled to discuss the lawsuit. A phone call was made from one to the other and communications opened. Instead of legal threats, Takada offered an alternate solution. He said that the place for wrestling’s differences to be decided isn’t the courtroom, it’s the ring.

By the end of the conference, it was made official. New Japan Pro Wrestling and UWF International would collide on October 9 in the mother of all arenas – the Tokyo Dome.

The company which had spent years claiming superiority to “fake” wrestling was now working with one of the industry’s titans.

One of UWFi’s wrestlers would take exception to this: Kiyoshi Tamura, the aforementioned rising star. While the UWFi had been negotiating with New Japan, Tamura was advocating for the company to go even further into the shoot-style concept and begin emulating the MMA fights fans were seeing on Pancrase events. The ever-proud Tamura completely refused to participate in the feud, resulting in him being made a pariah among his peers.

To the rest of the locker room, this was their last chance to stay afloat. Using New Japan’s massive popularity, the company could gain enough momentum to carry it out of the slump it was in.

A Desperate War

As a part of the feud, the coming weeks would see the two organizations publicly clashing over every detail of the Tokyo Dome show. Tensions heated when the card was announced and it featured a double title main event: Real World Heavyweight champion Nobuhiko Takada would go to war with IWGP Heavyweight champion Keiji Muto. At the end of the night, one man would stand on top of both companies.

It didn’t take long for the plan to go sideways. On October 2, seven days before the event, Nobuhiko Takada held a press conference where he made a stunning announcement. Wrestling legend Lou Thesz had left the company, and as it was his property, took the world championship with him. As UWFi no longer had a world title, the double title match was off.

The match was eventually made an IWGP championship match nonetheless, with Takada just being a challenger. The mystique of Takada’s potential IWGP title reign lived on in fans’ minds. His recent failures had disappeared from public consciousness in the face of this exciting new program.

The political reality of the partnership was evident when the show came to pass. Of the eight matches, UWFi won three. All of New Japan’s victories came by submission, and the majority of the matches saw the UWFi wrestlers dominated. While the main event was a much more even match, Muto still picked up the victory.

Though the show was a massive financial success and the rivalry between Takada and Muto would continue to even greater heights, it was clear that UWFi’s talent were second-class to New Japan’s. Due to their vulnerability, UWFi had very little power in the partnership, so New Japan’s booker, Riki Choshu – the same Riki Choshu that Akira Maeda kicked to break his orbital bone and reform UWF years ago – was the final say.

Takada was eventually able to capture the IWGP Heavyweight championship, but loss after loss destroyed the momentum of the other invaders. The partnership would end with a legendary title match between Takada and Shinya Hashimoto. With 65,000 fans in attendance, Hashimoto would hand Takada a resounding defeat to reclaim the title and send UWFi packing.

The company was left grasping at straws. A program between Nobuhiko Takada and veteran Genichiro Tenryu would bring in 41,087 fans to a September show, but UWFi was in such immense debt that the success meant nothing.

On December 21, 1996, Nobuhiko Takada announced that the promotion would close at the end of the year. Their final show on December 27 would see Takada standing tall in a UWFi ring one last time.

With his home promotion now gone, Takada considered his future. He was growing old, his star power was diminishing and negotiations with New Japan rival All Japan Pro Wrestling had fallen through.

Takada made a decision which would revolutionize the world of combat sports. After years of anticipation, he decided to avenge Yoji Anjo’s defeat and challenge Rickson Gracie.

Star Turned Martyr

Years had passed, but Takada was determined to finally make the fight against Rickson Gracie a reality – one that he knew could be among his biggest yet. Through connections with advertiser Naoto Morishita, TV event organizer Nobuyuki Sakakibara and businessman, ex-Yakuza member, and funder Hiromichi Momose, Kakutougi Revolutionary Spirits (which would eventually be closed, then re-opened with the same staff as Dream Stage Entertainment) was created in order to conduct what would become the first PRIDE event.

Though it was originally intended to be the only PRIDE event, PRIDE 1’s success would open the floodgates for future shows. Suspicions spread before the event that it would be a bomb, but they were proved wrong with an amazing turnout. Attendance was announced at 46,863 fans, though the likelier number (according to the October 20, 1997 edition of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter) ranged from 35,000 to 37,000 fans in attendance – still an overwhelming success.

Unfortunately for Takada, he did not share in the delight. He was a star (Commentator Stephen Quadros would compare his fights to if Hulk Hogan had taken up martial arts), but he was also an aging professional wrestler and not an experienced fighter as the public saw him. Experts gave him no chance of victory against Rickson.

While the Japanese and Brazilian national anthems were performed before the fight, Nobuhiko Takada showed something he never had: fear. He could not make eye contact with Rickson, a sharp contrast to Gracie’s stone-cold glare.

Five minutes later, Takada was forced to tap out to an armbar after an embarrassingly one-sided bout. His performance was universally criticized – media, fans and even Takada’s own trainers doubted his ability. In an attempt to salvage his popularity (which was still a large reserve to capitalize on, embarrassing defeat and all), Takada won a fixed fight before facing Rickson in a rematch.

At PRIDE 4, exactly a year later, Takada corrected his mistakes, faced Rickson with confidence, and displayed a much-improved skillset. He lasted four and a half more minutes.

Takada’s improved performance earned him some of his lost respect, but his reputation was still shattered and his star was rapidly fading. Another fixed fight was arranged, this time with inaugural UFC Heavyweight champion Mark Coleman. Though its fixed status was obvious to those with experience, Japanese fans began to regain hope.

In his next fight, he would drop an even more convincing loss to Coleman’s teammate Mark Kerr – who MMA experts had been discussing as one of the greatest prospects in the heavyweight division.

Takada was no longer expected to win. His star power was being used in order to create convincing stars out of legitimate fighters. As long as PRIDE needed him to survive, he was more than willing to let his reputation be destroyed. A new hero would have to be the one to change the tides of the rivalry between Japanese fighters and the Gracie family.

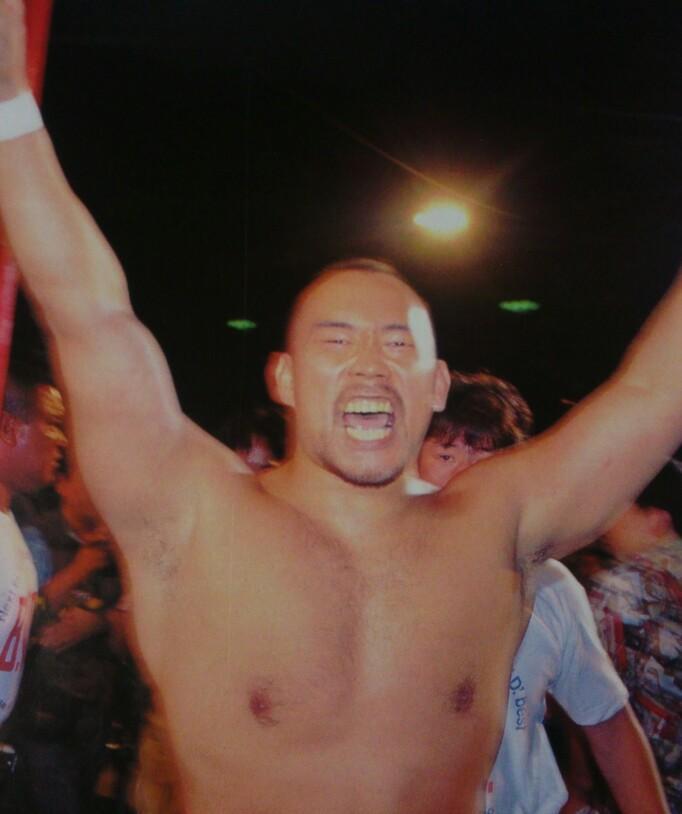

The Gracie Hunter

As Nobuhiko Takada’s popularity collapsed, a student of his was climbing the ranks. Fellow shoot-style pro wrestler Kazushi Sakuraba had increasingly impressive showings against legitimate competition. Displaying unusual charisma and incorporating pro wrestling techniques like the Mongolian chop and the giant swing into his moveset, Sakuraba went 5-0-1 in from PRIDE 2 to PRIDE 7. The latter four fights were against some of the best Brazilian fighters around, and Sakuraba either took them to the limit or defeated them in astounding fashion.

Sakuraba’s path led him toward a natural collision course with the Gracie family. At PRIDE 8, he defeated Royler Gracie by technical submission with a Kimura lock. Royler would refuse to submit, but the referee would call it off when it seemed that his arm was about to snap. It was the first defeat a Gracie had suffered in decades.

While the Gracie family was furious over the technical nature of the victory, Sakuraba skyrocketed to being the biggest star in all of mixed martial arts.

The victory would mark the beginning of a legendary rivalry between Sakuraba and the Gracie family. In avenging the losses of Yoji Anjo and PRIDE’s former protagonist Nobuhiko Takada, he had proved that Japan was just as strong as the Gracies claimed to be.

Though Royler’s defeat marked the beginning of the rivalry, its apex would be Sakuraba’s second challenge: a fight with the only three-time UFC tournament winner Royce Gracie. Though it was not a certainty – more on that in just a second – an unheard of ruleset was created for the fight at the demand of the Gracie family.

There would be no judges, no referee stoppages, and an unlimited amount of rounds. Should Sakuraba and Royce face off, there would be no doubt as to who was the definitive winner.

While the Gracie family viewed themselves as simply using the clout they had earned, the other fighters disagreed. According to Mark Kerr in a 2010 interview with Sherdog.com, “All of us were going to protest and say ‘no, we’re not going to do unlimited rounds’. They ended up compensating the fighters a little bit more money to just accept the rule.”

Kazushi Sakuraba spoke with Sherdog for the same article, saying “Let me say that it is due to expressionless Royce and his relative Rorion that we have this no-rules fighting. But isn’t it that this fire they lit has gotten bigger than them and now they are running away from it?”

Grand Prix

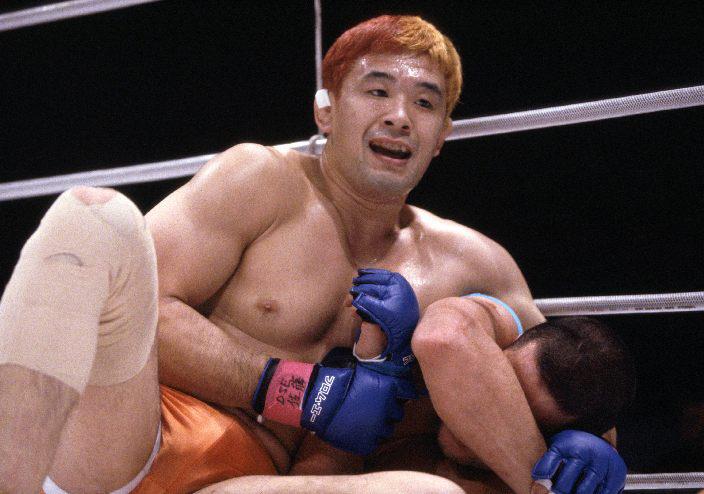

PRIDE Grand Prix 2000 – Finals.

Photo by Susumu Nagao.

PRIDE’s first events that were a true success after Takada/Rickson 1 were the PRIDE Grand Prix 2000 – an openweight tournament between 16 of the biggest and greatest fighters in the world at the time. The opening round was held on January 30, and the finals took place in one night on May 1.

In the opening round, Kazuyuki Fujita, a pet project of Antonio Inoki, made his MMA debut. Owing to what would become a legendary ability to take punishment, Fujita won in 2:48 to advance to the quarterfinals.

Though Nobuhiko Takada would face one of his last great tests in a disappointingly dull 15 minute decision loss to Royce Gracie, Kazushi Sakuraba would defeat Guy Mezger to advance.

The stage was set for the finals: Fujita would advance, and Sakuraba and Royce would have their anticipated clash.

Sidebar – Comparing Attendances

Both PRIDE Grand Prix shows were held at the illustrious Tokyo Dome, one of the most famous venues in Japan. The opening round drew 48,316 fans, which was possibly the largest mixed martial arts crowd ever up to that point. The finals would draw a smaller, yet still massively successful, number of 38,429 fans.

The decline is attributed by some to the absence of Nobuhiko Takada, who pulled out of a planned dream match against Ken Shamrock due to a knee injury suffered in his fight against Royce. Others point to the low quality of said fight, which garnered uncharacteristically loud boos from the Tokyo Dome crowd throughout.

In comparison to the two shows, New Japan Pro Wrestling’s April 7, 2000 Tokyo Dome event, “Dome Impact”, drew a crowd that was announced as 60,000. The number was decried as “clearly a face-saving fake number” by Dave Meltzer of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter (New Japan had a habit of exaggerating attendances well into the 2010s). According to estimates, the likeliest numbers were closer to 35,000.

New Japan’s January 4 “Wrestling World 2000” event from the dome was a legit sellout of 63,500, though as the January 4 show is a yearly tradition, it can be considered an anomaly. A third Tokyo Dome show was a similarly unique case: New Japan and All Japan joined forces as the top two companies in Japan for a cross-promotional feud, bringing in 64,000.

The anomalous shows weaken comparisons between the two fields. Not even “Dome Impact” can provide a framework to reflect with. New Japan drew what was believed to be “the smallest crowd the promotion has ever drawn in the building”, according to the Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Important to note, however, was that the show did a ludicrously massive TV rating.

In a situation I hope to touch on more in the next part, the main event retirement match between Shinya Hashimoto and Naoya Ogawa drew a 24.0 rating, the largest rating for a pro wrestling match globally since 1986.

Both fields are doing hot business at the Tokyo Dome, but one could also argue that both are seeing short-term successes for interesting individual lineups. At this point, mixed martial arts and professional wrestling are neck-and-neck on paper and anything but separate in reality.

Just to complete the picture, K-1’s 2000 Grand Prix on December 10 drew what was announced as an impossible 70,200 (in order to set an attendance record), but what was in reality still “likely well over 60,000” as per the Wrestling Observer. The tournament finals between Ernesto Hoost and Ray Sefo drew a 24.6 rating. The show overall drew a 19.6, which Meltzer notes was the “second highest” rating in the tournament’s history, second to 1997’s 20.7 overall rating.

From an American perspective, it’s easy to overlook K-1. Kickboxing doesn’t have the history or relevance here that wrestling or MMA do. However, K-1 is an absolute beast with an undeniable hold on combat sports. Just keep that in the back of your mind for context.

Grand Prix (cont.)

At the final, Fujita was matched up with Mark Kerr, who previously defeated Takada and was, again, one of the top heavyweights in the world. With little experience, Fujita scored a shocking upset by decisively overwhelming Kerr and winning a decision.

The fight has seen some controversy for some time. Kerr’s corner have claimed issues such as low blood sugar and a torn MCL hurt his ability to perform. I’m not aware if Fujita’s corner have commented on the injury, but I have to share Fujita’s comments on the fight.

Fujita told Sherdog.com that he thought if he could hold Kerr off for five minutes, he could take the advantage. He then commented on his own skills by saying that he didn’t “really have anything all that great, but in today’s vale tudo, the strongest is the one that can take a beating.”

Sakuraba and Royce Gracie would have a fight that would go down in MMA history. Over a full 90 minutes of fighting, Sakuraba not only survived Royce, he made it look effortless. In a fight where at different points, Sakuraba spun, laughed and pantsed his way to victory, Royce’s corner eventually threw in the towel.

Sakuraba’s victory was monumental. Speaking with Sherdog.com, play-by-play commentator Stephen Quadros recalled seeing even the fans in the far corners of the arena erupting with joy when Gracie was defeated. Quadros said it was “probably the most dramatic ovation I’ve ever heard in my entire career.”

Though Sakuraba would have to pull out of his next fight after 15 minutes due to exhaustion, his status as a superstar was solidified.

In the finals, yet another star would be crowned. In a far cry from being on such a downturn he had to accept a fixed loss to Takada, Mark Coleman won the Grand Prix and earned the right to officially be considered the greatest fighter in the world. Based on his achievements alone, Coleman became a massively popular and menacing figure in combat sports.

Bridging The Divide

In the aftermath of PRIDE’s greatest success, pro wrestling’s contributions were undeniable. Sakuraba was the most popular fighter in Japan, and he had not only incorporated pro wrestling into both his fighting style and his personality, nor had he just transitioned from wrestling to MMA. Sakuraba fought for professional wrestling’s honor.

Not only had the unstoppable Gracie Jiu-Jitsu philosophy been defeated by a pro wrestler, others had become stars or cult favorites in his wake. Naoya Ogawa’s fame and reputation were affirmed by MMA victories, Alexander Otsuka and Dajiro Matsui became cult favorites, and, of course, Kazuyuki Fujita rocketed to stardom.

As much as the two communities may look down on each other in the modern day, there’s no question that wrestling and MMA owe much to one another.

At PRIDE 9, the natural connection was finally made. In a special appearance, Antonio Inoki was welcomed into the ring for an announcement. That New Year’s Eve, PRIDE would join forces with professional wrestlers to present the first annual Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye show. The only pro wrestling show in what would later become an annual mixed martial arts event, it would see mixed martial artists stepping into professional wrestling’s field, evening the playing field created by wrestling’s success in MMA.

Ahead of PRIDE’s next event, Inoki was appointed executive producer of Dream Stage Entertainment, making the partnership official. At the next two events after his appointment, PRIDE 10 and PRIDE 11, it almost seemed as if Inoki’s presence brought good fortune to his fighters. Though Tokimitsu Ishizawa (aka Kendo Kashin) and Kazunari Murakami both suffered losses, Ogawa and Fujita both took home impressive victories.

Ogawa would avenge Kazunari Murakami’s loss by defeating Masaaki Satake, a famous kickboxer who had made his MMA debut earlier in the year. The fight suffered from allegations of fixing, but the energetic Japanese fans paid no attention to anything besides Ogawa’s victory.

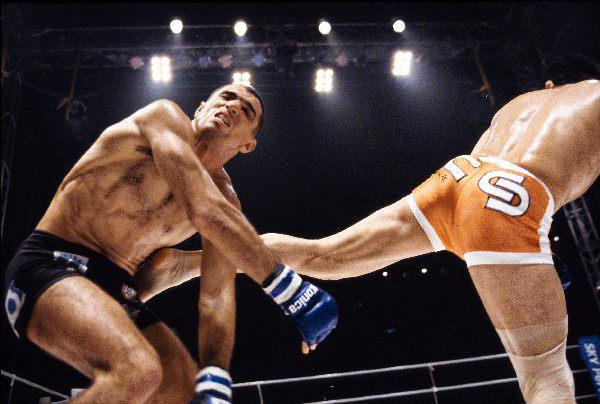

Kazuyuki Fujita, however, would have even more massive prey: Ken Shamrock, former UFC champion fresh off his time in the WWF.

In a wild and exciting confrontation, Fujita made a series of unbelievable comebacks. In the first exchange of the fight, Shamrock seemed to have landed a punch that knocked Fujita silly. Instead, Fujita just shook his head and kept coming.

At one point, Shamrock had locked Fujita into a tight guillotine choke. His face turned purple, blood was dripping from his nose, and still Fujita didn’t drop. As the crowd roared his name and Antonio Inoki looked on, Fujita pushed his way out and kept coming.

Despite the massive amount of punishment Fujita took, his unbelievable ability to take damage led him to victory. He continued to pressure Shamrock.

Six minutes into the fight, Fujita was tied up with Shamrock against the ropes when Shamrock called for his team to throw in the towel. The fight had made the legendary Shamrock suffer heart palpitations, giving Fujita the TKO victory and scoring a tremendous upset.

A Final Stop

There would be one more roadblock on the road to Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2000. PRIDE 12: “Cold Fury”, held a mere eight days before the former event on December 23, 2000, featured much of the talent who had been rumored to participate in Inoki’s show.

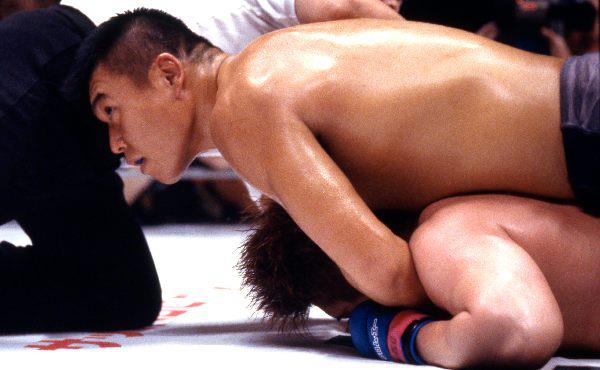

The biggest such name was Kazushi Sakuraba, who was scheduled to face Kendo Kashin at Bom-Ba-Ye. He continued his victories over the Gracie family by defeating Ryan Gracie by unanimous decision. Ryan had previously defeated Kashin (fighting under his real name of Tokimitzu Ishizawa) earlier in 2000.

The planned match between Sakuraba and Kashin was designed to try and save Kashin’s momentum with a competitive showing. In storyline, the two had animosity dating all the way back to the feud between New Japan and UWFi. Sakuraba lost twice to Kashin (also then using his real name) by submission while representing UWFi, and this would be their first meeting since Sakuraba’s rise to stardom.

Shortly before the show on December 18, Sakuraba received a historic accolade. He was crowned Tokyo Sports’ Most Valuable Player, a prestigious award which crowned the year’s most significant professional wrestler.

Of course, Sakuraba was no pro wrestler at this point in his career. There was no strict separation of pro wrestling and mixed martial arts in Tokyo Sports’ awards, though there was an immensely heavy bias toward pro wrestling. For being a former wrestler who set the world on fire with his victory against Royce Gracie, Sakuraba qualified well enough.

After accepting the award, Sakuraba publicly pitched a change to his match against Kashin: either he would team with Kashin against Renzo and Ryan Gracie, or he would team with Ryan against Renzo and Kashin.

However, this plan would fall apart in the days before the fight, likely when Ryan Gracie would suffer a shoulder injury while sparring. He still fought, of course, but there was no way he’d be talked into pro wrestling.

A less fortunate name planned for both shows was Mark Kerr. The very-recently-former MMA top prospect fought Igor Vovchanchyn, one of, if not the, hardest hitting fighters of all time. For context, Vovchanchyn’s punches have been said to be so powerful that they don’t even hurt; a hit from Vovchanchyn is more like cracking your windshield with your skull during a car crash than being punched in the face.

They fought a long battle that went into overtime, where the tides turned. What had been a balanced affair became a slaughter as Vovchanchyn landed more and more against Kerr. Kerr wasn’t knocked out, but he lost the decision after the final round.

Due to the damage Kerr took, there was talk of replacing him in his planned match (where he would team with best friend Mark Coleman against New Japan’s Yuji Nagata and Takashi Iizuka). Kazuyuki Fujita, who had also fought on the show in a low-impact fight against Gilbert Yvel, was in better condition and was the pick for Kerr’s substitute.

Kerr continued on to the event at his own request. Surprisingly, Fujita would not appear in any official capacity after becoming one of Inoki’s breakout stars over the year.

Other fighters on the show also appear at Bom-Ba-Ye. Alexander Otsuka, who suffered a quick knockout loss, faces Ricco Rodriguez, who won a unanimous decision, in a tag team match. Here, Akira Shoji loses a decision and will go on to participate in a tag match himself.

With only eight days to go until the event, there are no further complications. However, there is one fighter nowhere to be seen on PRIDE 12 who will have something of a last hurrah: the original star himself, Nobuhiko Takada.

To complete the tale of Takada’s return and enter Bom-Ba-Ye 2000, we’ll have to turn our attention to the other half of his double life: the world of professional wrestling. More importantly, we’ll have to turn our attention to his biggest rival, and consequently, to the United States.

Facing a crossroads in his career and a multitude of nagging injuries, a Japanese legend took drastic measures and left the country. Headed to the United States, changes had to be made – and so the Great Muta was reborn. Follow the path of pro-wrestling to Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2000, next time on “Bom-Ba-Ye”!