Engage with Western fans of Japanese wrestling enough, and you’ll begin to hear about the so-called “dark ages” of New Japan Pro Wrestling. It’s a nebulous label with no strict range of years included, but it is understood by most to mean New Japan’s early 2000s. Under Antonio Inoki’s lead, New Japan’s focus shifted from a product that emphasized in-ring work and long matches to one that prioritized realism and success in a different field: martial arts.

Inoki is said to have become obsessed with mixed martial arts, promoting poor wrestlers with MMA notoriety over the long-tenured and more deserving members of New Japan’s roster. Inoki’s philosophy – known as “Inoki-ism” – caused a downturn in business and eventually tanked the company’s reputation.

Simultaneously, All Japan Pro Wrestling – historically New Japan’s biggest competition – went into turmoil following the death of longtime owner Giant Baba and mass exodus of their roster to form a new promotion. A desperate All Japan turned to legendary wrestler Keiji Muto to boost their business, crowning him as the company’s President. However, Muto’s time spent wrestling in the United States led him to push sports entertainment as the winning formula over All Japan’s classic style, alienating the fans and almost killing the promotion.

But that’s just the popular narrative. While it’s commonly accepted to be the case, is it as true as many might think? Did Inoki intend to sacrifice New Japan to build a reputation in martial arts? Did Muto really fall victim to his own foolishness? Where exactly do these narratives transition from fact to legend, and how much of that legend needs to be questioned?

I intend to first address the history behind wrestling’s mix with MMA before discussing where the two fields intersected during the J-MMA boom of the early 2000s, then leading in to the discussion around the first show of this review series.

I’d like to acknowledge potential weaknesses for this project before continuing. I’m an American living in the US with little knowledge of Japanese, so my sources and experiences are predominantly based on/biased to a Western perspective. Throughout this project, I’ve done my best to incorporate Japanese sources whenever possible – using either manual translations or machine translation with a very heavy dose of caution on mistranslations. I invite feedback and recommendations for sources to check.

The Foundations

By the turn of the millennium, professional wrestling and combat sports were inseparable – no matter how much proponents of either field wished or claimed otherwise. Each field had begun to incorporate more and more of what could be seen in the other: pro wrestling adopted the tap out instead of the verbal submission and wrestlers such as Ken Shamrock, Tazz, and Shinya Hashimoto began to reach stardom based off of a legitimate or perceived background in martial arts. MMA took inspiration on how to build their events and stars from professional wrestling, using wrestling tropes to build hype and preferring charismatic fighters to skilled ones.

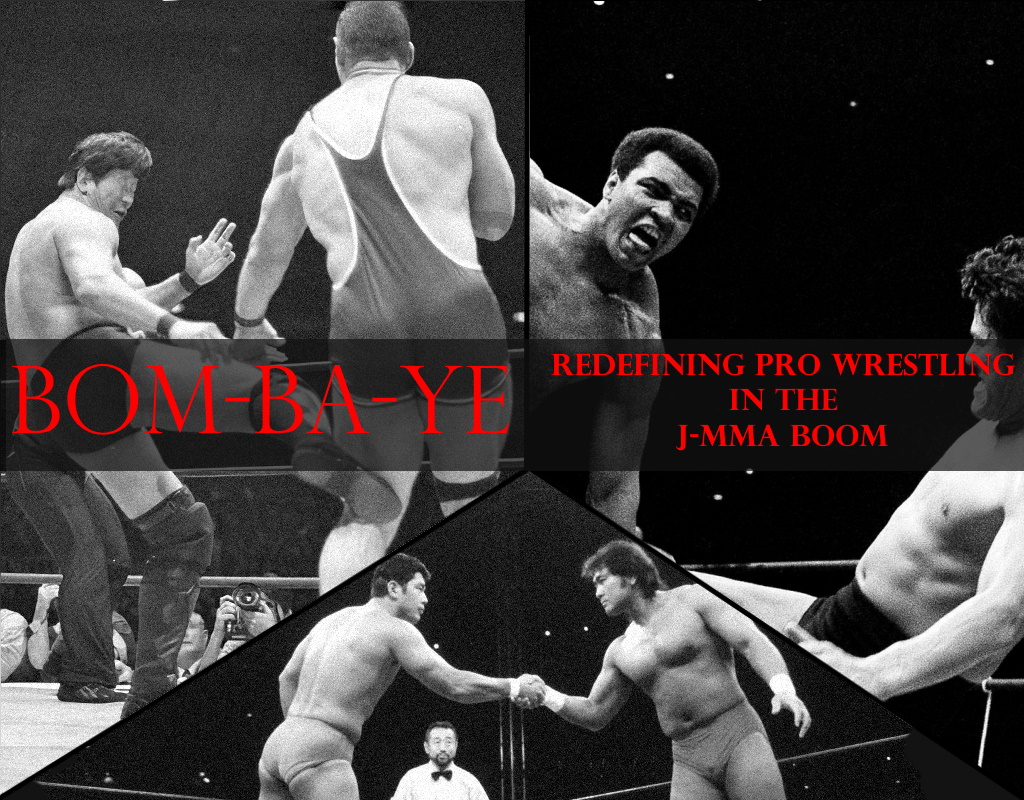

The interplay between wrestling and MMA was no recent development in 2000. It actually predates mixed martial arts as a whole; in fact, pro wrestling is where we can see MMA begin to take shape. Across the course of his long career, Antonio Inoki participated in multiple “different style fights” – matches pitting him against martial artists. He faced off with numerous legendary fighters under pro wrestling rules, but it was his shoot (legitimate) fight against Muhammad Ali that laid the groundwork for MMA.

Inoki would defeat martial artist after martial artist – Olympic gold medalists, judo champions, and sambo wrestlers – with every victory serving one purpose: to establish professional wrestling as the strongest art (or the “King of Sports”, as New Japan’s branding states), and Inoki as its champion. This, I would contend, is the true beginning of the “Inoki-ism” philosophy.

Shoot-Style Takes Hold

Inoki’s different style fights date back to the 1970s, and the “King of Sports” mentality would take root in much of Japanese professional wrestling. Wrestlers who were proficient in the “shoot-style” that bridged the gap between wrestling and martial arts became wildly popular, with Akira Maeda and Nobuhiko Takada being notable names. The success of the shoot-style allowed for promotions such as UWF and UWFi to develop a strong cult following.

Seeing the success of the shoot-style, Inoki laid the groundwork for a famous “incident” in 1999. Judo champion and Inoki protégé Naoya Ogawa was set to face Shinya Hashimoto, a superstar with a martial arts based style. The match was immediately evident as a shoot. Ogawa was laying in strikes on Hashimoto while Hashimoto, with little real martial arts experience, did his best to defend himself. A barrage of strikes left him bloodied on the outside, and the match was called off.

Soon, the ring was packed with representatives of both New Japan and Universal Fighting-Arts Organization, Ogawa’s team. After tensions began to ease, New Japan matchmaker and legend Riki Choshu stormed into the ring and confronted Ogawa, eventually slapping him. An all-out brawl broke out between the two promotions, seeing at least one wrestler hospitalized afterwards.

Some claim that this match was Ogawa purposefully ruining Hashimoto’s reputation to boost himself, either on his own or at Inoki’s request. However, it’s more likely that Hashimoto had agreed to the idea. The close friendship between Hashimoto and Ogawa and the numerous matches they would have afterwards seem unlikely if Ogawa really had ruined Hashimoto’s credibility at New Japan’s biggest show of the year.

The success of people like Maeda, Takada, and Ogawa serves to prove that the “Inoki-ism” philosophy does work. By making wrestlers seem like legitimate fighters, they can reach legendary levels of stardom. In fact, it’s the ability for pro wrestling to make stars where we see the other side of this story take root.

Enter The Boom

Across the 1990s, the mixed martial arts promotion PRIDE Fighting Championships (PRIDE FC) and the stand-up fighting promotion K-1 had steadily become some of the most popular acts in Japan. K-1, which innovated the grand production value that would become a centerpiece of pro wrestling, surpassed then-number-one promotion New Japan in the late ‘90s. PRIDE, itself born from the ashes of Nobuhiko Takada’s UWFi, was created to hold a fight between Takada and jiu-jitsu legend Rickson Gracie and would establish a massive MMA brand based off of that event’s success.

Both promotions began to run into obstacles when the major stars they had established began to show their age or become unable to fight. K-1’s biggest stars had declined, passed away, or left for PRIDE or pro wrestling, and PRIDE saw Nobuhiko Takada’s entire aura destroyed after convincing losses in his fights with Rickson. As they began to realize that their success may not be sustainable, the two began to plan for the future.

K-1 President Kazuyoshi Ishii may be the most important man in this project. After he began to worry for the long-term viability of K-1, he began to enter other ventures to make money. Among other things (which will become very relevant soon enough), Ishii tried to shake the reputation of being just the K-1 promoter.

Ishii entered pro wrestling and mixed martial arts by serving as the agent of current and future stars such as Don Frye, Bob Sapp, and Bill Goldberg. These names were major draws at the time, and Ishii guaranteed success for himself by tying his name to theirs. His financial anxiety is an inciting act for pro wrestling’s response to the Japanese MMA boom of the early 2000s, but it is also what ends the period once and for all – more to come on that later.

Worlds Collide

Equally anxious are PRIDE’s parent company, Dream Stage Entertainment. Headed by Naoto Morishita, Dream Stage were of the opinion that the drawing power of their stars peaked after they reached their physical peak, meaning that they were limited by their ability to perform to a top level. In their minds, the answer was clear – pro wrestling.

Dream Stage had seen how wrestling could make people like Takada into stars, and thought that it would be the best way for them to take advantage of and protect their past-their-prime fighters. PRIDE would create the stars, and pro wrestling would cash in on them.

This, then, leads directly into the first show of this project: Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2000. It would be a New Year’s Eve show pitting PRIDE fighters against professional wrestlers, live from the Osaka Dome. In honor of the new millennium, Antonio Inoki – a legend to pro wrestling and mixed martial arts – was going to bridge the divide between the two worlds, seemingly changing them forever.

Before the “Inoki-ism” period, before Keiji Muto gained power in All Japan, and before Kazuyoshi Ishii entered pro wrestling, the first revolution of the Bom-Ba-Ye era took place on December 31st, 2000. What went into this historic event, and was it as revolutionary as either side hoped? Find out next time, when Bom-Ba-Ye meets its namesake event for the first review of the series.